Those in Orlando who had seen the unmarked face of the warehouse at 47 W. Jefferson St. probably considered the property abandoned. And then, on that Thursday afternoon in 2013, it blew up.

Witnesses are scarce two years later, but here are the undisputed facts: A ruptured tank storing an experimental cooking gas called hyrdillium was the source of the eruption. The address was registered to the robotics and gaming company Creative Engineering Inc., though no one was inside at the time of the blast. Two trains passing through a station three blocks away were held up for 180 minutes until investigators could be sure the area was safe. One witness described the shockwave as “more intense than a thunderstorm.”

Local man Tim Roth later told The Orlando Sentinel he rushed into the mess before fire, police, or EMTs made it to the scene, looking to rescue survivors. Instead of human bodies, he found mangled, furry animatronic limbs twitching in the rubble, and flaming gorilla heads as big as beach balls in sluggish rotation.

It was, the paper reported, “as if the Joker’s lab had exploded.”

“It was pressure and rust.” So says Aaron Fechter, founder and sole remaining employee of Creative Engineering, when I meet him at the warehouse 18 months later. He is kneeling over the remains of the tank, which is split open on the floor of his warehouse like a discarded banana peel.

“Rust worms. These tiny little rust worms that eat through things like a drill. I’d caught them twice before but this third one, well…” Fechter smiles instead of finishing the sentence. Above us, a white milk bottle remains trapped between the roof and rafters, thrown between the two by the explosion in the split second before the ceiling slapped down again. The warehouse is mostly restored—which depleted Fechter’s bank accounts—minus a wall on a shared property line with neighboring business Doctor Phillips Charities, who Fechter says went to court demanding it be demolished as structurally unsound. (The charity did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

Had you seen the wall when it was still standing—and you are of a certain age—then there is a good chance you would recognize a mural of Fechter’s most famous creation: robot band The Rock-afire Explosion, the glory of birthday parties at more than 200 domestic Showbiz Pizza restaurants in the 1980s. But even if you never went to a Showbiz (or a Chuck-E-Cheese, which bought out the chain years ago), you know the man’s work. Right now, somewhere, a gleeful child is smashing a diminutive mammal face in a Whac-A-Mole cabinet game, which Fechter invented. According to Fechter, at least. The people who sell that game now say otherwise.

Had you seen the wall when it was still standing—and you are of a certain age—then there is a good chance you would recognize a mural of Fechter’s most famous creation: robot band The Rock-afire Explosion, the glory of birthday parties at more than 200 domestic Showbiz Pizza restaurants in the 1980s. But even if you never went to a Showbiz (or a Chuck-E-Cheese, which bought out the chain years ago), you know the man’s work. Right now, somewhere, a gleeful child is smashing a diminutive mammal face in a Whac-A-Mole cabinet game, which Fechter invented. According to Fechter, at least. The people who sell that game now say otherwise.

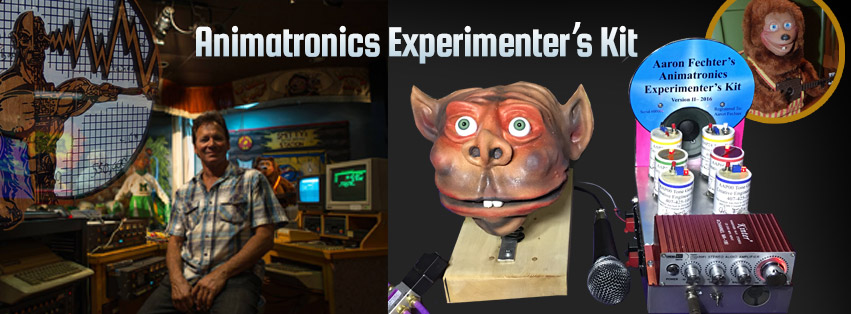

Decades have passed since both of those strange sagas. I’m in Orlando today because Fecther is near completion of a new invention. A game he believes can restore his rightful dominion over the crumbling empire of America’s arcades and save the now-endangered menagerie of the Rock-afire.

The shelves are crammed with solenoid actuators with spring bars and pneumatic rams and camshafts and 9-volt batteries. There are still rows of maroon tanks filled with experimental chemicals. He has saws and soldering irons and a dozen Apple II computers. He’s set up to mold hard rubber. He could build anything, really, but will give me only a cryptic description of his latest device before our meeting.

“It’s smart. It’s something I think adults will enjoy. It’s a robotic brain, mechanical, not a computer. And it’s going to be relevant to the post-apocalyptic challenges I think we’re all expecting.” Before he allows me to see it, he demands a promise of confidentiality on camera that I will keep his work secret until he’s ready to unveil it publicly this fall.

Finally, Fechter steps aside and lets me take the controls. The device isn’t even painted yet. Only the barest elements that constitute a game are here now. As I focus on the electronics and wood in front of me, he turns on a small camcorder set up behind me to record the player’s experiences. Later on, he’ll use the video and my feedback to fine-tune the game’s robotic nerve center.

While playing, I ask myself: If I were a 10-year-old at the arcade, and I had fistful of quarters, would I stick with Fechter’s game and earn some prize tickets, or head for Mortal Kombat?

I don’t know if it’s the next Whac-a-Mole, but it’s fun and challenging. I tell Fechter he’s not wasting his time.

“God, I’m glad to hear you say that,” he says.

Carnies and Suckers

Every November, Orlando hosts the International Association of Amusement Parks & Attractions Convention, a weeklong celebration of amusement park food and technology. More than 25,000 people are registered for the conference, which transforms the Orlando Convention Center into what must be the world’s largest pop-up theme park, filled with the latest free rides, game, and food. It’s safe to assume they could make a solid profit if they decided to charge general admission.

Instead, the attendees are split between vendors trying to sell their wares and businessmen looking to upgrade their parks. The latter group can be boiled down to two types: the reps who stock parks like Six Flags and Adventurelands, and the smaller operations who let the bigger fish worry about innovation and are after downmarket versions of already-successful games. There is a strict “No Photography” policy to prevent the real threat of stealing someone’s idea. A sale to the right person this week can make a game if not an overnight success, then at least immediately profitable. That’s why Fechter is racing the clock to finish up his new contraption.

On the first day of the convention, Creative Engineering’s registered booth at number 4435 is empty. With 48 hours before the doors are opened, Fechter’s new game has stopped working.

Even if Fechter’s new game is a wild success, it would be nearly impossible for it to match the cultural impact of the Whac-A-Mole. It’s one of the few games that transcended the arcade to become cultural shorthand, so much so that it’s one of President Obama’s favorite rhetorical devices to explain his war policy. Yet if the game proves to be even a modest success, he could make more money than what he earned from the iconic rodent-bopper—a miserable $2,000. The story of why is one that sounds so pulled from the pulp pages that you’d wouldn’t believe it if it weren’t about carnies.

It started at the 1976 IAAPA convention, he says, where a 22-year-old Fechter was hoping to find work. “I met this carnie, this guy named Denny Denton,” Fechter remembers. “And he says, ‘Ah you know how to build games? Come with me, let me show you something.'”

Denton guided his new friend to Booth 13 where a group of well-dressed Japanese men where hammering away at the insides of a cabinet game. For whatever reason, the machine kept freezing up on them during what should have been a major showcase. The game had about half-a-dozen cartoonish animal creatures that were supposed to spring forth from fist-sized holes for players to hammer.

Fechter believed he could make something similar for Denton that worked. Less than a month later, Denton was on the couch of Fechter’s one-bedroom Orlando apartment waiting to take the finished product back to his carnival backers.

With one week left to go, Fechter says he came home to Denton loading a .45 Magnum at the kitchen table.

“There two kinds of people in this world, Aaron,” Denny Denton told him. Fechter remembers him poking bullets into the chamber of the .45 Magnum. “There are carnies and suckers. And you ain’t a carnie.”

Fechter delivered on time and thought that was that. But unbeknown to him, his client took the design and sold it to Orlando’s gaming business Bob’s Space Racers, who marketed it to great success.

“I was a kid, I didn’t understand how to protect myself,” he says. “I didn’t know it was going to be this phenomenon. And I want that street cred, you know, I want them to acknowledge it when I roll this new game out. ‘The new game from the man who brought you the Whac-A-Mole.'”

“I was a kid, I didn’t understand how to protect myself,” he says. “I didn’t know it was going to be this phenomenon. And I want that street cred, you know, I want them to acknowledge it when I roll this new game out. ‘The new game from the man who brought you the Whac-A-Mole.'”

Despite my best efforts, Fechter’s story resists fact-checking.

Denton the carnie is AWOL. Fechter says after the game was delivered his client returned to the Florida town of Gibsonton, and they never saw each other again. But knowing Denton’s home base offers few leads. Known as “Showtown U.S.A.” among tradesmen skilled in ring toss and skeeball, Gibsonton is the winter home for carnies waiting out the offseason. The percentage of traveling showmen who call it home is so high that this is the only municipality in the country with residential areas zoned to accommodate the keeping of elephants.

Doc Rivera is curator of the town’s International Independent Show Museum, a position informed by his 50 years hustling rubes. In his opinion, the odds of finding Denton are about as good as finding an honest fortuneteller. Assuming Denton exists. “There are a million stories on the midway and that’s one of them,” he says of Fechter’s account. “You have to understand, carnival owners stick around. But staff, that’s like McDonald’s staff. They might be there a week, three months, then they move on. Plus half the time they’re going by nicknames. Blackie, Whitey, Slim, Shorty.” Fechter’s records include a deposit amount listed for $2,000, but nothing that spells out what he was paid to build.

Back in 2015, Bob Space Racers, which credits itself as “creators and developers” of the Whac-A-Mole, has its own untroubled display at the 2015 IAAPA convention, not even a three-minute walk from Creative Engineering’s stand. At the sound of Fechter’s name one of the company’s executives mutters, “Total bullshit.”

On the last day of the convention CFO Michael Lane agrees to an interview. Lane says that until a few years ago, no one at the company had ever heard of Aaron Fechter. “By his own admission he doesn’t know who the guys are. The name he has isn’t even correct,” Lane says. “So all I can tell you is, I hope he sells a lot of those games. He says he’s the inventor of the Whac-A-Mole. He’s not the inventor. He even admits someone else was at this convention who had come up with the idea for the game.”

Lane, who did not work for the company until nearly a decade after the sale, says the game really originated with two men bringing them a non-working model. Bob’s Space Racers got it running and started manufacturing cabinets. Whether Fechter ever had any contact with those two men, Lane can’t say. Bob’s Space Racers sold the license to Mattel years ago.

“I don’t know how much of what he says is true. I don’t know specifically what his conversation was with these guys,” he says. “But as far as I’m concerned he defames us in some ways. I don’t want to say what we will do and won’t do but I don’t think that’s right. I went by his booth Wednesday and left my card and asked for him to come talk to me. I haven’t heard from him.”

Lane admits that he’s withheld giving Fechter the names on Bob Space Racer’s contract for the Whac-A-Mole. But at the end of our interview he slides the document over to me, a deal made in the late 70s with one Donny Anderson of Tennessee and Gerald D. Denton of Texas. “I have no idea what happened to them,” Lane says.

Regardless, Fechter’s biggest success was still ahead of him. March 3, 1980, the day the first Showbiz Pizza Place opened its doors in Kansas City.

An Animatronic Star Is Born

The Rock-afire Explosion’s story follows the familiar beats of an episode of Behind the Music: Struggle, sudden fame, then the crash. The golden age was 1983, when Fatz Geronimo and his robot pals served as the in-house band at every ShowBiz Pizza. Creative Engineering’s annual revenue that year was more than $4 million. Employees kept beach towels in their cars for the days Fechter decided he and his employees would be more productive after an impromptu splash in the Atlantic. Michael Jackson visited company headquarters between tours supporting Thriller.

If you were a kid celebrating a birthday at Showbiz Pizza in the 1980s, here is what you’d find: Center stage is Fatz Geronimo, the silverback gorilla keyboard player whose instrument is wired with a lightshow to flare in time with his chord progressions. Fatz is flanked to the left by Dook LaRue, a man-sized dingo drummer in a space cadet outfit, and to the right by surfing polar bear guitarist Beach Bear, drunken oil drum fowl and vocalist Looney Bird, and gossipy mouse cheerleader Mitzi Mozzarella. The face of the band, country-fried bass playing bear Billy Bob Brockali, gets his own showcase stage to the right, while on the left-hand side is a private showcase for stand-up comic/ventriloquist wolf Rolfe deWolfe and dummy Earl Schemerle.

The band’s act was a robotic vaudeville: cheesy jokes, Saturday morning cartoon covers of whatever was topping the charts, and a gender-neutral rendition of Happy Birthday. Fechter himself sang most of the parts, but recruited some ringers. Beach Bear vocalist Richard Bailey would spend up to 70 hours a week recording music for arcade-addled kids. (He went on to find success beyond the furry suit as touring guitarist for boy band LFO, singers of the immortal lyric “I like girls that wear Abercrombie and Fitch.”) Fechter and Bailey entertained themselves with the meager joys of smuggling dirty jokes past their corporate overlords and injecting postmodernism into childhood pizza parties. “Leaves audience confused and bewildered,” read one critique from the Showbiz head office when shown a scripted routine in which the band has a fight after the curtain had closed. A lyric about Santa busting his sack on the way down the chimney made it into a Christmas show without inquiry. Small triumphs.

Bailey didn’t realize how popular his animatronic avatar had become until he and Fechter opened a new location in to Muskogee, Oklahoma. Fechter was used to the road, flying to each new location and zipping into his Billy Bob bear costume like a glam rocker applying his make-up backstage. But Bailey was unprepared for the swarms of preteens vibrating on the triple threat of soda, birthday cake, and video games, burning out their sugar rush over his music. After the restaurant’s doors shut on its first day of business, Bailey and Fechter found the waitresses admiring of the duo.

“The prettiest one drove me to the airport,” he remembers. “I think that’s when I realized, ‘OK, maybe this is something.'”

In 1989, the wave crests. That year, Showbiz realized it was losing money and made a hasty merger with Chuck E. Cheese. Fechter’s new bosses told him they’d keep his characters if he signed over the rights. He refused, believing the Rock-afire Explosion was on the verge of lucrative television, film, and record deals. “If I gave them rights … they would’ve let [the robots] rot and taken them down, and then nobody could bring them back because they’d own them,” he says.

Hollywood deals failed t

o materialize. Fechter’s subsequent inventions faltered. He invested $1.5 million in a secure email device called the Anti-Gravity Freedom Machine that was clearly ahead of its time. He released it in 1991, when almost no one knew what his product did. The layoffs started. Computers started to go missing from the office, along with electronics, welding equipment, and at least one case filled with tools.

The Revival

Showbiz Pizzas close. The world moves on. But nothing can break nostalgia. Armed with the power of YouTube and eBay, two Rock-afire fans sparked a perfectly odd mini-revival 20 years after Fecther’s creation disappeared from the public consciousness.

David Ferguson grew up spending afternoons and weekends at Showbiz Pizza franchises, easy to recognize in the front row carrying a portable tape deck he would use to record the shows for home reenactments. Now a 37-year-old defense contractor, he purchased a number of secondhand Rock-afire robots off Ebay. But it wasn’t to put them on the shelf and forget about them. He developed software that could be used to activate the entire band for performances.

Chris Thrash, a roller rink DJ in Alabama, likewise grew up a Showbiz devotee. By the time he met Ferguson, he had already bought a complete set of Rock-afire members. Thrash used Ferguson’s software to program a contemporary setlist for the band. They were strange. They were wonderful. They were perfect for YouTube.

The first Rock-afire video he posted to You Tube was set to Bubba Sparxxx’s “‘Miss New Booty.” All the elements were there for a viral hit. While thirty- and forty-somethings indulged in the videos’ goofy nostalgia, kids who’d never heard of Showbiz Pizza marveled at the uncanny valley weirdness of seeing crude animatronic robots from another lifetime belting out hip-hop. It was like seeing late-career Johnny Cash crooning Depeche Mode’s “Personal Jesus”—just bizarre enough to be amazing.

“Miss New Booty” got 80,000 views. A second clip, set to Usher’s “Love In This Club,” pulled in more than a million. Suddenly, magazines like Spin and Wired were publishing stories about Fechter’s work again. He was getting attention from both barons of irony and aging fans who remembered those Saturday afternoon birthday parties. It sounds like a godsend for a career in need of a jump-start.

“I hated it,” Fechter says. “That was my first reaction. Absolutely hated it. Those were adult songs. That’s not the Rock-afire audience.”

Fechter’s believes Ferguson’s software is a direct assault on his rights to the characters, because it allowed fans and potential competitors to take control of the robots away from Fechter. Ferguson, meanwhile, says the whole point of his project was to give people the tools to keep playing with the toys they loved as kids.

“David’s my Whac-A-Mole,” Fechter says. “[If] he pops up again I’m going to bring that hammer down. Even though I sued him, he still has a show. What’s he going to have when he plays it? My voice coming out of his speakers.”

Despite his hostility, the rediscovery of Rock-afire did wonders for Fechter. After Fatz Gorilla and his bandmates were accidentally rebranded as a hip nostalgia act, Cee-Lo Green booked the act to back him in at a Vegas performance. Ryan Gosling included them in his directorial debut, Lost River. Country singer Shooter Jennings’s fandom ran so deep that he promised to produce an album of the group’s new material, an offer Fechter believes will be made good in the next two years.

Still: “I’m scared,” Fechter says. “I’ve had so many failures. I’m so scared this is just going to be

another. If I lose this place that’s the end of the band. I still can’t get credit for the Whac-a-Mole. And then I think, ‘Well, I’m just the guy who made the Mezmerizer game that no one wanted and that’s that.'”

Before I left his warehouse that first night, Fechter insists on one last Rock-afire performance, a medley from The Beatles’ White album. We sit there and listen as the band sings: I listen for you footsteps, coming up the drive. Listen for your footsteps, but they don’t arrive. Waiting for your knock dear, on my front door. I don’t hear it. Does it mean you don’t love me anymore?

Near the last hours of Tuesday’s debut in Orlando, Fechter meets an old fan. The Ripley’s Believe It or Not rep with the shaved head and fashionably tight blue suit grew up on The Rock-afire explosion. “I love your work, I recognized you from the documentary,” the man introduces himself. “What do you have?”

Fechter barely stops to breathe as he leads off with the game’s malfunction, then segues into the now-well-rehearsed script. “But I said to myself ‘Aaron, are you going to let some blob of soldering metal steal your happiness?” Fechter says he wants to get Bashy Bug into production by mid-2016. The Ripley’s rep tells him he loves the look of it. “Will you give me a call when you get it working? I’d love to see it.” Fechter gets a business card.

By midday Friday, as the convention is reaching the finish line and almost everyone has boarded a flight home, Fechter has made no sales, but remains optimistic about Bashy Bug’s chance for success. In the intervening days he has put up a laptop with footage of test players so buyers could see the game in action.

He still has not spoken to anyone at Bob’s Space Racers in person.

Before I leave Florida, I visit a Chuck E. Cheese on International Drive. Fechter’s prediction on the company’s future seems to have proved out. The entertainment is pre-recorded song-and-dance routines on massive flatscreens, looped. I don’t see many robots or Whac-A-Moles.

I suspect Fechter’s already back at the game, where he’ll be again tomorrow and the day after. Some nights he’ll be there alone in his workshop, program a show, and wait for Billy Bob Brickell’s curtain to open. The voice singing back to him will be his own.

— excerpt from Popular Mechanics – February 3rd, 2016